Colorado ghost towns hold endless fascination for both residents and visitors alike. There’s something about poking around these old sites, where publicly accessible, and imagining what life was like in the 1800s that holds us captive to the memories of those who came before us.

Colorado is lucky to have a number of well-preserved mining towns such as St. Elmo in Chaffee County (9,961’); Ashcroft in Pitkin County (9,500’) and Animas Forks in San Juan County (11,200’) that beckon many visitors during the accessible seasons of summer and early fall. These three ghost towns, among others such as “Uptop” or Old La Veta Pass, are either all on the National Register of Historic Places or are located in Historic Districts that offer intact, standing buildings to explore.

However, Park County has few if any buildings that remain of its 80 plus ghost towns, primarily because of nature’s elements. Given the high altitude and harsh winters, most of the fragile wood structures have dissolved back into the earth, leaving only some old boards or a foundation outline as evidence of what originally stood there.

Although there aren’t any fully intact, standing ghost towns in Park County, we are lucky to have many original and/or restored buildings in the South Park City Museum that give the visitor a true taste of what life was like. Open from spring to fall, this is a living history museum well worth exploring and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2014. A number of towns remain today that were able to establish themselves as permanent communities such as Park City, Alma, Jefferson, Guffey and Fairplay.

View this post on Instagram

Park County, one of the first 17 counties created by the Colorado Territorial Legislature in 1861, had no less than 80 small communities from 1859 through the twentieth century. Some were no more than railroad sidings, stage stops and ranch post offices while others became thriving communities that still exist today. Although none are on an Historic Register, our local haunts are just as significant with some fascinating stories to tell.

What is a ghost town? Philip Varney, a well-known ghost town book author, defines a ghost town as: “Any site that has had a markedly decreased population from its peak, a town whose initial reason for settlement (such as a mine or railroad) no longer keeps people in the community.”

View this post on Instagram

Park County’s towns and mining camps were established as commerce hubs, for mining in the early days and ranching and railroading soon thereafter. Some newspapers engaged in “booming” the new town by calling it a “city” in numerous articles in hopes of drawing prospective residents to the town. Montgomery and Puma were both “cities” although the former is now at the bottom of Montgomery Reservoir and Puma City is but one large cabin.

The proverbial boom and bust cycle was prevalent here as it was in most mining towns throughout the West. Gold was discovered in 1859 north of Como at Hamilton/Tarryall and west of Fairplay in Buckskin Joe. The mineral played out in the late 1860s but there was a resurgence in the early 1870s when silver was discovered on Mount Bross, located in the Mosquito Range. This was actually the precursor to Leadville’s famous boom.

Three ghost town sites worth visiting today are Hall Valley in the northwest section of the county, Buckskin Joe in the west and Puma City in the north central area. All three can be reached via a regular car although the ride may be bumpy in places.

HALL VALLEY

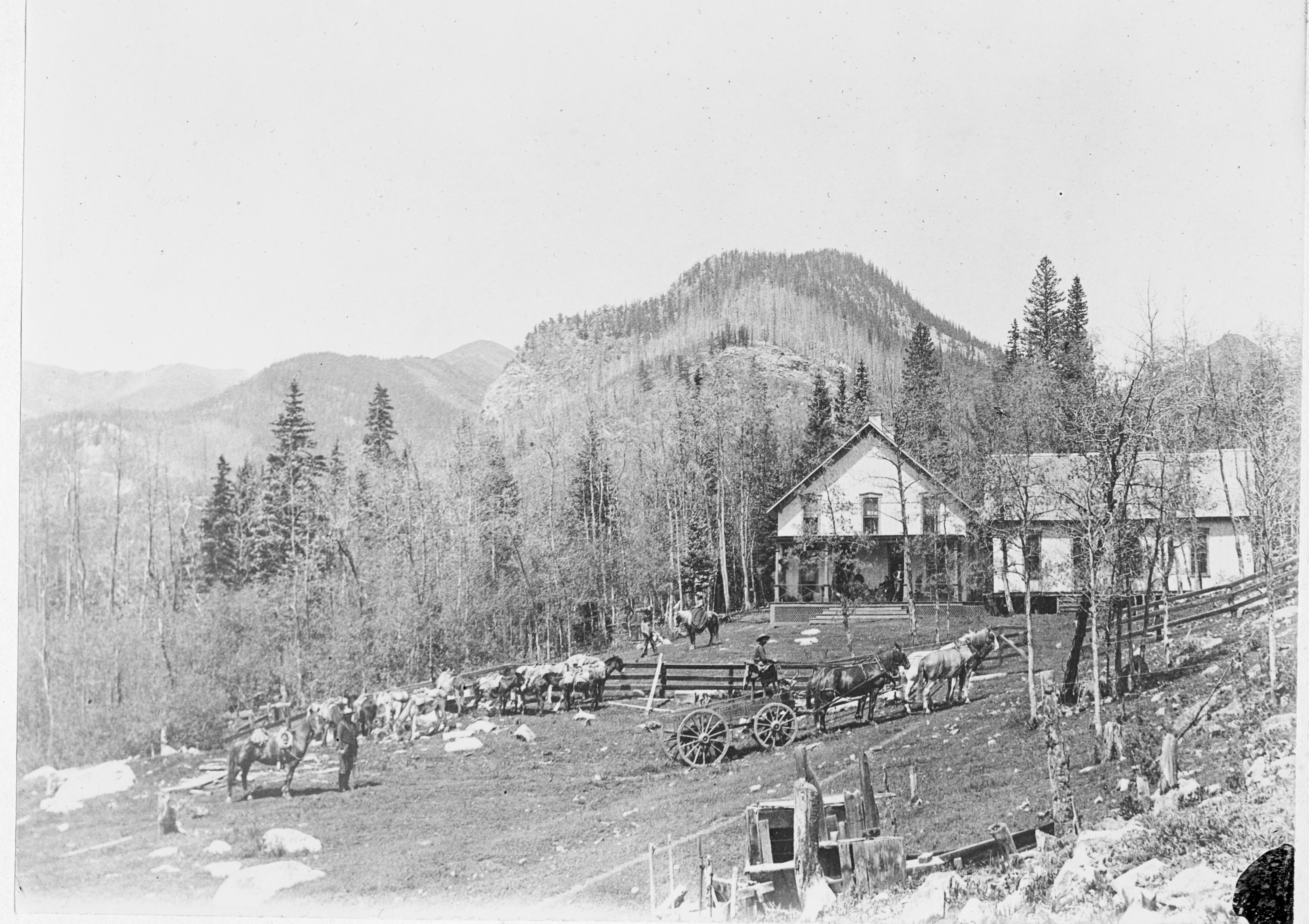

The bustling town of Hall Valley, circa the 1870s, showing Colonel Hall’s family home. Source: Park Co. Local History Archives.

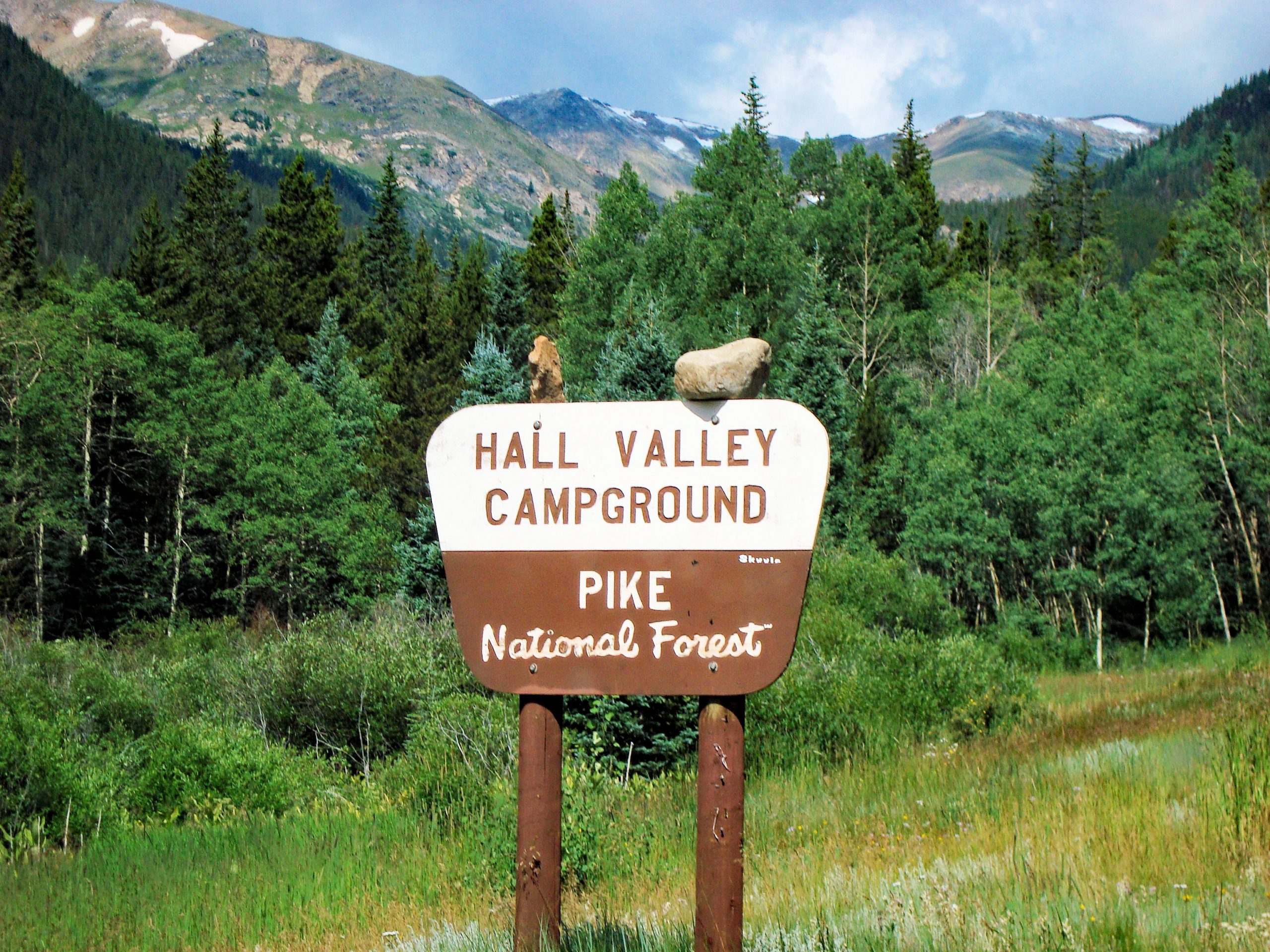

The campground sign welcomes visitors to the former site of Hall Valley, also known as Halls’ Valley and Hallsville. Whale Peaks is in the distant background.

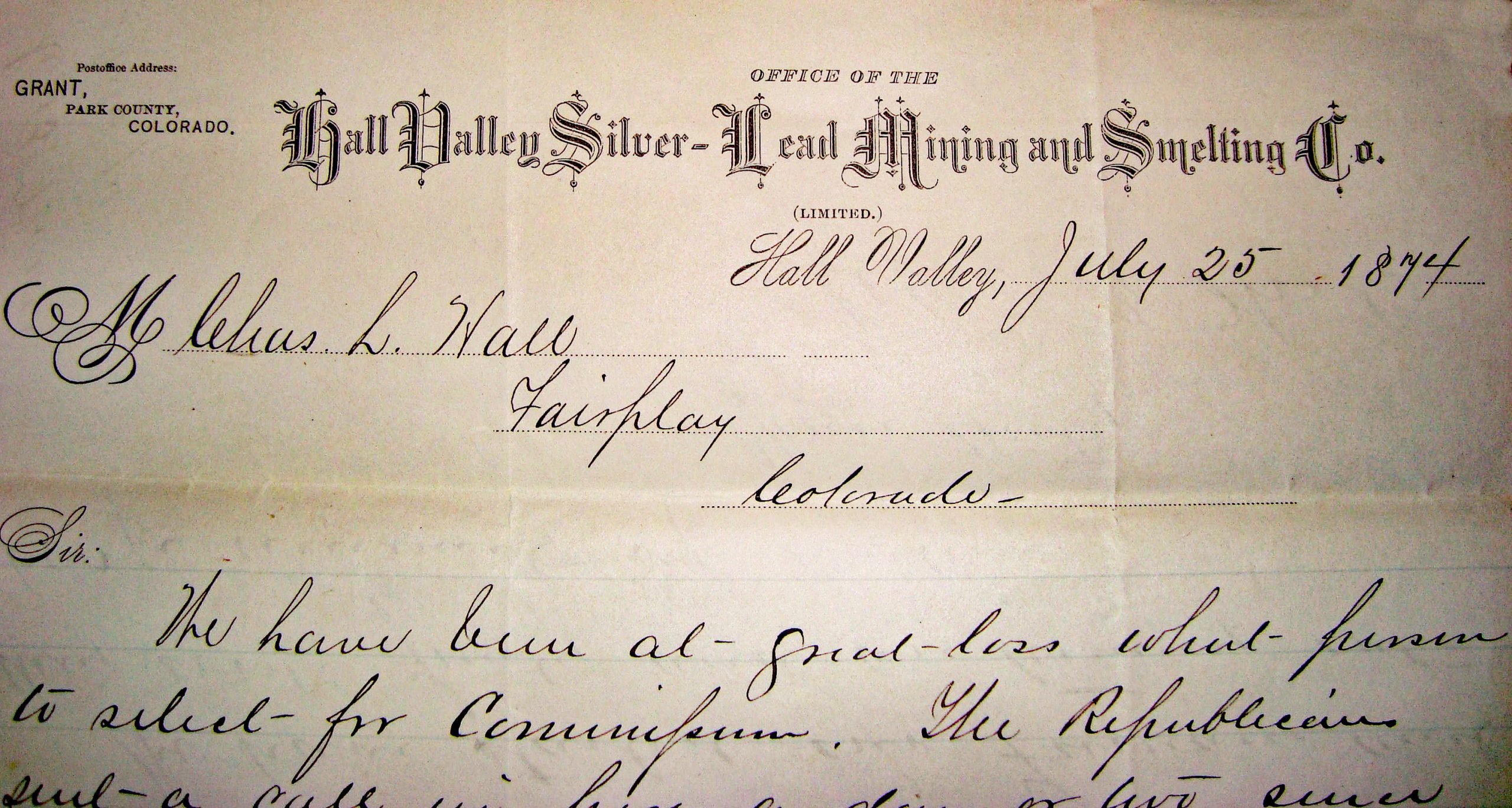

Hall Valley, now located in the Hall Valley Campground, was established by Colonel Jairus W. Hall in 1872 after silver was discovered near Whale Peak in the Whale Mine. A Brigadier General who hailed from New York, he preferred the name of Colonel. Hall was a principled man with a large backing of wealthy British investors. He formed the Hall Valley Silver Lead & Smelting Company and built an extensive tramway and smelter. During the height of silver production in 1883, the mine produced 13,000 oz. of silver.

View of the campground nowadays where Hall’s house once stood in front of the trees on the right.

However, the smelter was not designed properly for the particular type of silver ore and the entire camp was eventually abandoned. In its heyday however, there were boarding houses, a huge reverberatory furnace, stores and saloons. The latter typically lead to trouble which it certainly did in 1883 when “Big Jake’ Bayard, shot and killed one Amos Brazille in George Campbell’s saloon after a disagreement.

The letterhead from the Hall Valley Silver-Lead Mining and Smelting Co. Circa 1880.

To see the townsite today, take State Highway 285 west from Bailey for approximately 14 miles and bear right on CR 60, Hall Valley Road. Continue on this private gravel road for 5 miles and turn left into the Hall Valley Campground at the sign. As you stand in the center of the campground facing west, the houses and other buildings were just ahead to the right.

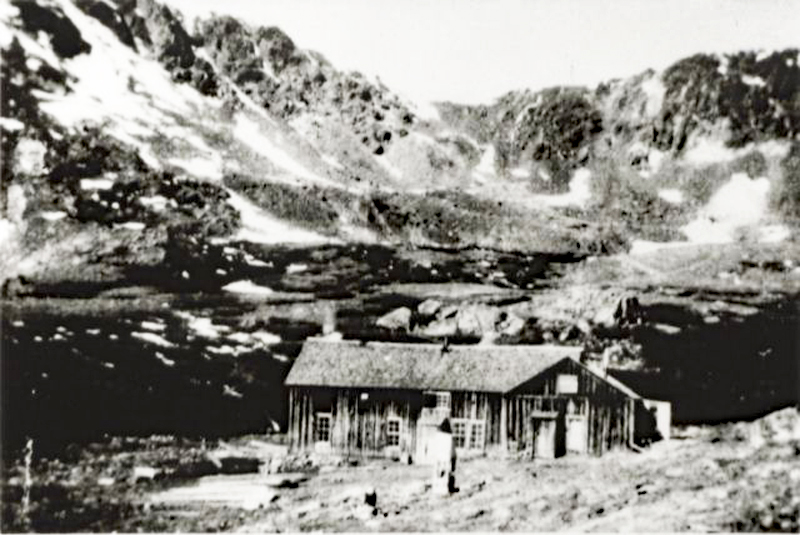

The Whale Mine boarding house at timberline in the early 1900s (no longer standing). This was the second boarding house; the first one was demolished in a February 1879 avalance. Source: Park Co. Local History Archives.

PUMA CITY

A rare photo of the Puma City stage that ran daily from Jefferson along the Tarryall Road, making the 35-mile journey in 5 hours in 1897. Note the wood building on the right looks fairly new. Source: Park Co. Local History Archives.

Puma City was a late bloomer, founded around the time of Cripple Creek in 1894 when gold, and later beryllium, was discovered in the Puma Hills/Tarryall section. These hills are well-named since the red rocky outcrops provide a perfect environment for the puma or mountain lion.

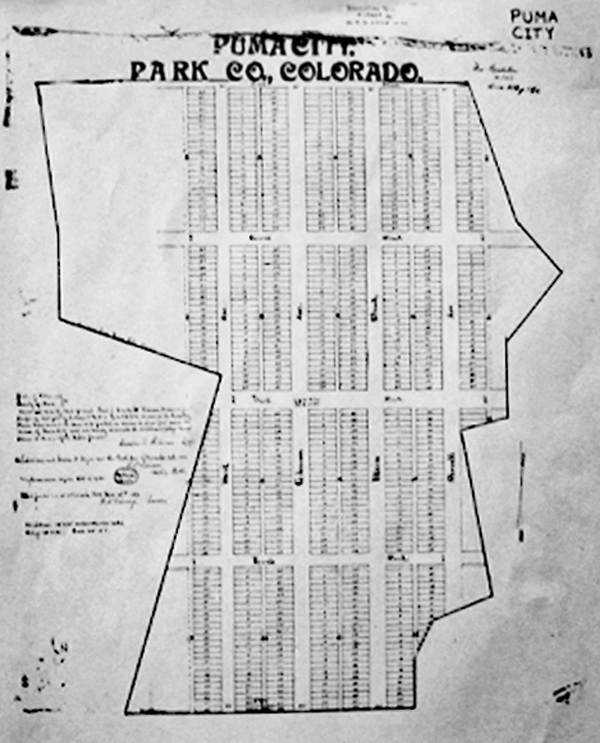

A faded copy of the Puma City plat map, date unknown. As with many pioneer “cities,” the town never approached the size shown here. Source: Park Co. Local History Archives.

The town of Puma City, located on County Road 77 or the Tarryall Road, was created in the early spring of 1896 after the Gilmore brothers and George A. Starbird from Victor, Colorado came north, prospecting along the way. The group soon found gold and other minerals and started the mining settlement.

By December of 1896, Surveyor A.G. Hartman with the U.S. Surveyor General’s Office was in town, surveying properties to ensure the townsite and mining claims were properly aligned to avoid any later confusion. Twenty businesses and residences had popped up and approximately one hundred men were prospecting in the hills. Three weeks later, the number of buildings doubled. The Midland railroad station in Lake George was a jumping off point for passengers to disembark and then catch a four-horse stagecoach to Puma. This thirteen-mile journey took over two hours.

Photo of Sid Derby’s general store and Post Office, taken approximately 30 years ago by Lake George resident and historian, Steve Plutt.

As with all mining districts, the gold played out in 1899 but several stalwart citizens remained, one being Mr. Sidney Derby. Thinking that a resurgence was coming in 1922, he bought up the entire townsite and made his home in the general store and attached Post Office. Derby died 9 years later and is buried in the Lake George Cemetery.

To see the old townsite today, drive approximately 12 miles west of Lake George on County Road 77 (the Tarryall Road) until you see the cabin in the photo below, the remains of Derby’s store and home. Please not that this is on private property, so only view the site from your car or the roadside.

BUCKSKIN JOE

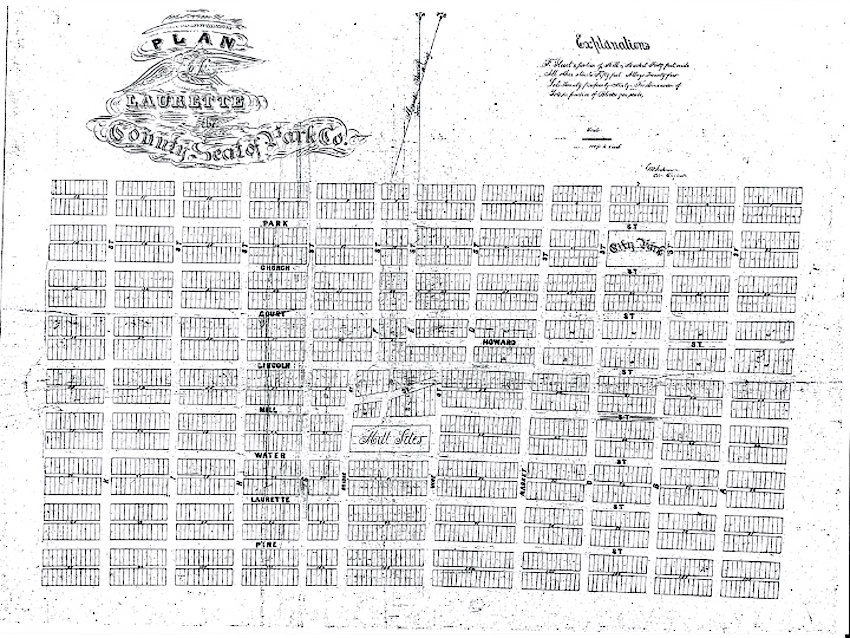

The Buckskin Joe mining camp was settled in the early 1860s during Pikes Peak Gold Rush. Originally named Laurette, the many miners who swarmed into the gulch preferred the nickname of Buckskin Joe in honor of Joseph Higganbottom (or Higginbotham), a local mountain man. Higganbottom reportedly shot at a deer in the gulch but the bullet missed, striking a gold vein instead and exposing the rich ore. He was known to wear buckskin clothing and thus the name stuck.

One of the only two known photos of the original Buckskin Joe mining camp, taken in 1864 by Denver photographer George D. Wakely. Source: Park Co. Local History Archives.

The second photo by Wakely that interestingly, does not include any people in the scene. Source: Park Co. Local History Archives.

The town was described as a “fast city” according to the Rocky Mountain News in February of 1862, boasting a population of several thousand. Nothing remains of the camp now – a few old mine dumps, a long row of rocks that lines a once well-traveled street and some square-cut nails here and there. But in its heyday, “Silver King” Horace A. W. Tabor and his first wife, Augusta, called Buckskin Joe their home for several years.

After the gold played out, the town was abandoned but had a brief resurgence before being abandoned altogether. The courthouse cabin was moved from Buckskin to the South Park City Museum and Tabor’s store went to the Royal Gorge tourist attraction called the Buckskin Joe Frontier Town, but that is now gone as well.

To visit the original site of Buckskin Joe, drive 7 miles west of Fairplay on Highway 9, then turn left in Alma onto CR8, Buckskin Street. Drive approximately one mile and look for a gravel road on the right with a cemetery sign. Turn right and you’re in the town. Continue on this road a short distance to visit a beautiful old pioneer cemetery.

A copy of an early plat map of the town of Laurette, later Buckskin Joe. Source: Park Co. Local History Archives.

Local ghost towns and ghost town sites are an important tribute to the pioneers who came before us. Although many of the towns no longer exist, the locations are still interesting to visit and provide a window into our pioneer’s determination to forge a new life in Colorado.

If you’re not able to visit one of these historic locations in person, there are a number of excellent books on Colorado ghost towns for some intriguing armchair travel.

When you do visit a site, please abide by the courtesies of no trespassing if the site is on private property and do not take any physical souvenirs.

Park County’s history lives on in the remains of its original settlements.